I couldn’t make the trip seven years ago, when the last total solar eclipse happened over the continental US, but I promised myself that I’ll make it to the next one. Since this is a very special event that I’ve never seen before, I also decided to go all out and try to do something that possibly has never been attempted before by any one person - making images of the same totality in a daguerreotype and in wet plate collodion negative, which historically were the first two major photographic processes, wet plate replacing daguerreotypes in 1850s.

To the best of my knowledge, the first time a total solar eclipse was photographed by Julius Berkowski in 1851in Königsberg Prussia, while the first wet collodion image was achieved by Warren De La Rue in Spain year 1860. Neither of those gentlemen used a conventional camera, and, unlike myself, had access to major funds or/and institutions. After doing a bit of calculations in my head, it occurred ti me that it’s likely possible to just use a large format camera and a telephoto lens. I knew that my result would likely pale in comparison to those of the Royal Prussian Observatory, but the challenge and the thrill of even trying this were too tempting to pass up this once in a lifetime opportunity.

I won’t bore the reader with too many details of the drive, but I will say that it was long and brutal. The trip lasted 99 hours, in which I covered 3575mi (5720km) of road. I drove from San Diego to Oklahoma City, and from there decided to head for southeastern Missouri, as the radar was predicting highest chance of clear skies to be in that general area. When there, not far from the tiny and beautiful town of Doniphan, I found a great quiet spot to set up my two dark boxes, at The Narrows access to Eleven Points River, away from crowds and noise.

The larger dark box houses equipment for daguerreotype fuming and developing, while the smaller one has been my go-to wet plate location box for over a decade now.

The camera is Zone VI 8x10 with a 4x5 reducing back, and the lens is a 1896 Carl Zeiss Tele-Tubus IV, with 225mm Protar positive and 100mm negative elements. This lens has the finest brass work that I’ve ever seen and a shutter so complicated that two of the top repair shops in the country sent it back saying they had no clue how to approach something like this, but then I did find Carroll of Flutot’s Camera Repair in Los Angeles, and she did fix it beautifully. Brass work and shutter aside though, this is a wonderful lens. By varying the distance between positive and negative elements, it allows user to vary focal length anywhere from about 1600mm up to infinity. You do have to vary your bellows length, but, it being one of the very first telephoto designs, your bellows will be significantly shorter than what you would need for normal lenses at any given focal length.

The process of creating for me is a spontaneous one. The decision to involve both processes came to me only about a few weeks ago, and all the planning was done in my head, with zero testing other than fitting the lens to the camera and seeing that I’ll get an image do the size I pretty much expected. The last time I made negatives with wet plate color on was probably 5-6 years ago, it’s been all positives since then. I have also not made any serious attempts at making any daguerreotypes in the past year, when last spring I was again defeated in my ongoing quest to systemize and gain full control over the full spectrum of possible opalescence. That pursuit is proving to be so difficult that it literally put me off making plates for a year (though I think this little adventure might have reinvigorated my zeal). So, with that in mind, I was going to be happy with simply experiencing totality and going through my favorite motions in life while at it, getting any semblance of an image with both processes would be proof of concept that indeed this can be done with no extra special equipment and by one person with no team.

First off, I must say that the moment totality hits is not one you can prepare yourself for if you have never experienced it before. Just prior to it, I aligned my camera and checked focus the best I could, then ran over the dark box to prep the glass plate. I was pouring collodion when full totality arrived, and thankfully, as I imagined, there was just enough light for me to not miss the silver tank. The race was on, and the final mark was 3 minutes away. After dashing back to the camera, I exposed the 6 daguerreotype plates that I polished and fumed about half an hour prior. Which taking some minimal precautions not to disturb the camera and throw it out of focus, this took me about two minutes, at which point I darted over to the dark box to retrieve the collodion plate from its silver bath and placed it in holder. With the final plate in my hands I paused to gaze at the spectacle that was unfolding above me; and it was truly magical. I allowed myself about 15 seconds of awe. There anre many descriptions of totality and its incredible beauty, but, reallty, it’s indescribable. Trying to put into boundaries of language is akin to the inevitable shortfalls that even the best poet-philosopher would encounter while describing being in love. I was truly taken aback by what I saw, and I have seen a lot of beauty in this marvelous world. All of a sudden, in the perfect silence that was abound, an owl, thrown off by sudden onset of darkness, hooted twice nearby. This brought me back to reality, and I remembered that I still had a sensitized plate to expose, so I snapped this with my phone before making the last few steps toward my optical apparatus.

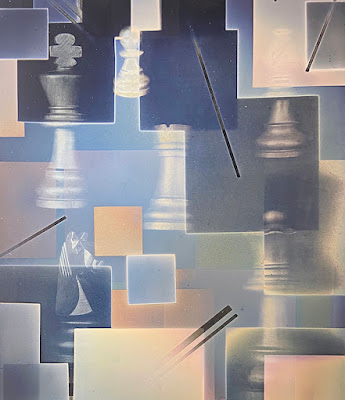

Two seconds into my last exposure the sun made its reappearance, at which point I promptly places the lens cap back on, and hurried back to the dark box in order to promptly develop the plate and see if anything came out. As I developed the negative, and through the red windows of my box saw daylight returning rapidly to Earth, I was gradually rewarded by seeing an image appear before me, and within a minutes and a half I had my negative secured. A bit later, after a good wash, I used one cycle of iodine redevelopment to boost density just a bit in order to print it via gelatin silver with lithographic developer. Here’s the negative still being rinsed, and then dried and held against dark background, and so shown there as overexposed positive

My exposures were 4-6 seconds, and the lens was being used in a configuration that gave me an approximate focal length of 2100mm and f11. At this magnification, the sun moves rather quickly across the plate; and so any longer of an exposure would have significantly blurted the image, in all past images with these techniques tracking devices were used for this reason. With such short maximum exposures a combined with relatively slow speed of my lens, I really didn’t expect much of anything to show up on my daguerreotype plates, I took the whole exercise as, quite literally, a shot in the dark. Working with daguerreotypes is not easy under any conditions, but doing it from a car on location truly does add a whole extra set of difficulties, including judging fuming colors as well as image during development. At first I didn’t see any discernible image on any of my daguerreotype plates. While being somewhat disappointed (I couldn’t have been too mad, I just saw totality and I knew I had a wet plate negative in the rinse), I decided to not fix out the plates, and carefully placed them back in their holders, in order to later take a better look at them back home, in hope that I’m missing something. Indeed, upon fixing followed by careful inspection in the darkroom, I found that all six plates had depictions upon them. Some were stronger than others, but there was image on all tries. This made the mission of capturing totality on both mediums truly complete, and so I gilded three of the best plates and here is a rather poor copy of one of them.

I’m still not a hundred percent sure of how I will finalize these three plates, and of the choices I’ll make while making lith prints from the collodion negative, but I’ll be sure to post an update on this post once it’s all finalized. I’ll likely meditate on that for a while, and let the plates themselves lend me a suggestion or two. As of now, I’m glad I tried this, and I’m over the moon that I got results with these venerable photographic techniques.

Good light to all,

Anton